| Program Category | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health centers | 872 | 630 | 530 |

| Patients | 5 million | 5.3 million | 6 million |

| Funding | $320 million | $383 million | $500 million |

Organizational changes

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare became the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 1979. As the 1980s began, community health centers were managed by the Bureau of Community Health Services (BCHS) in the Health Services Administration. In 1982, this agency merged with the Health Resources Administration to form the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). BCHS became the Bureau of Health Care Delivery and Assistance (BHCDA).

BCHS and then BHCDA were led by Dr. Edward Martin. Dr. Martin had helped found a health center in New York, before being recruited in 1974 to lead the National Health Service Corps (NHSC). Within a year of his arrival, Dr. Martin became the director of BHCS. He oversaw the community health center program, NHSC, and other programs until 1989.

Data collection

Dr. Martin and other early leaders created data collection and oversight policies for the program. These became the template for later practices, which the program still follows. They have proven essential for demonstrating the program’s effectiveness.

Bureau Common Reporting Requirements

Beginning in 1978, health centers began to provide information under the Bureau Common Reporting Requirements (BCRR). They reported the number of patients they saw, the number of visits, what services were provided at each visit, income and expenses, workforce, and a few other things. Compared with later reporting requirements, BCRR was minimal. For instance, there was no reporting on clinical outcomes. But it represented a big step for the program.

Some health centers found this reporting easier than others. But it was the collection of data—first through BCRR and later through the Uniform Data System—that helped the bureau show it was acting as a good steward of federal funds. This data also helped the bureau target resources where they would have the biggest impact. It let them offer technical assistance to health centers in areas where they were falling short.

Regional autonomy

Throughout the 1980s, the community health center program was managed mostly at the regional level. HRSA had a strong network of regional offices and fewer staff in the national headquarters. Project officers were close to the health centers and could visit easily. In addition, regional leaders were familiar with local issues and could respond to local challenges.

But over time, more control shifted to the national level. There were concerns about inconsistent policies and unclear funding decisions. In 1989, Congress centralized the grant award process within BHCDA. This meant application packages, policies, review criteria, and timeframes would be the same nationwide.

Partnership organizations

NANHC/NACHC

A group of health center administrators founded the National Association of Neighborhood Health Centers (NANHC) in 1971. Its primary mission was to provide training for health center staff and board members. NANHC received its first training contract from the Office of Economic Opportunity later that year. Training for health center leaders was important. BCHS wanted to ensure that health centers were well run and had adequate financial management systems in place.

NANHC changed its name to the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC) in 1977. Today, they continue to provide health centers with training and technical assistance, as well as resources, education, and coordination.

Primary Care Associations

The Health Center Program is also assisted by a network of state and regional Primary Care Associations (PCAs). The first were founded in the early 1970s in New York and Massachusetts. Like NANHC, they received funding from the government to provide training and technical assistance to health center leaders and staff.

In the early 1980s, NACHC began helping health centers in other parts of the country found their own PCAs. By 1986, there were 42 state PCAs and nine regional ones. Today, they continue to ensure that health centers in all parts of the country receive the training and technical assistance they need.

Potential changes to funding model

Initial proposal

In February 1981, President Ronald Reagan proposed combining 88 programs into seven major block grants. Community health centers and migrant health centers were among them. States would control the funding, with more limited federal oversight. In addition, the total for each block grant would be 25% less than the fiscal year 1981 (FY81) appropriations for all the included programs.

Congressional involvement

Months of negotiations in Congress led to a compromise. Health centers would continue as a federal grant program in FY82. Then, in 1983, states could apply for block grants to take over funding of their health centers. However, only two states applied for a block grant: Georgia and West Virginia. Georgia’s application was ruled non-compliant with federal requirements, and eventually West Virginia gave up its application.

Congress continued to fund the program each year as a federal grant program.

The HIV/AIDS Epidemic

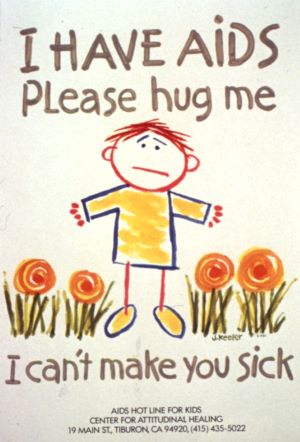

A new disease

In September 1982, the CDC identified a new disease named the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

“It wasn’t as well known,” recalls Regan Crump, a nurse practitioner at South Baltimore Family Health Center in the early 1980s who later worked in HRSA. “Early on, we just treated patients for the symptoms. With more cases of wasting in 1984, we then referred to the health department or specialists.” Treatment options were limited. “We had one drug, two drugs. It was a while before triple treatment came out.”

“New patients appeared suddenly and died quickly,” according to Margaret Flinter, a nurse practitioner at Community Health Center, Inc. in Middletown, Connecticut. “Fear was everywhere. It is hard to convey how much concern there was on the part of the health care establishment, especially dental and medical providers.” But her health center’s board refused to turn people away: “When others were refusing treatment to at-risk individuals, our board took the right course of saying we needed to act to serve everyone and to protect everyone to the fullest extent we could.”

Government responds

The government issued guidance on the “universal precautions.” These included handwashing, wearing gloves, masks, and other protective articles, and safe needle handling and disposal. In 1986, HRSA provided its first targeted funding in response to the epidemic. This would grow into the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a key part of the nation’s public health response to the virus.

Many of HRSA’s first responses to HIV were managed under BHCDA, which became the Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) in 1992. BPHC handled grants for community-based early intervention services, dental reimbursements, and AIDS Education and Training Centers. In 1997, HRSA brought all the parts of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program together under the new HIV/AIDS Bureau.

Federally Qualified Health Centers

Throughout the 1980s, health centers struggled to collect reimbursements from Medicaid and Medicare. State payment rates and eligibility criteria often limited the amount health centers could receive. Health centers took a big step towards fiscal solvency at the end of the decade when a new reimbursement category was created. As Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), they could receive higher reimbursements.

Increased reimbursements

Congress created the FQHC designation for Medicaid in 1989 and Medicare in 1990. All HRSA-funded health centers became eligible for cost-related reimbursement rates. Services by physicians, as well as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, clinical psychologists, and clinical social workers, were all covered.

Over the next few years, Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements began to replace federal grants as the largest source of income for most health centers. In 1990, federal grants were more than 40% of health center revenues. By 1998, it was down to 26%. Today, it’s around 19%.

Look-alikes

The FQHC designation also included a new category: Health Center Program look-alikes. Look-alikes meet all the requirements of health centers funded by HRSA under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, but they don’t receive funding from HRSA. However, look-alikes can get FQHC reimbursement rates and some other benefits health centers receive.