| Program Category | 1966 | 1971 | 1975 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health centers | 2 | 150 | 127 |

| Funding | $2 million | $155.4 million | $196.7 million |

Expanding economic opportunity

The Health Center Program grew out of the Civil Rights movement and the War on Poverty under President Lyndon Johnson. In August 1964, Johnson signed the Economic Opportunity Act. This law established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) within the Executive Office of the President.

At first, OEO focused on schools and jobs. However, program leaders soon realized that poor health among students and job seekers would prevent or limit participation in OEO programs. They began to look for ways to improve basic health among the disadvantaged and underserved communities in the United States.

Roots of the health center movement

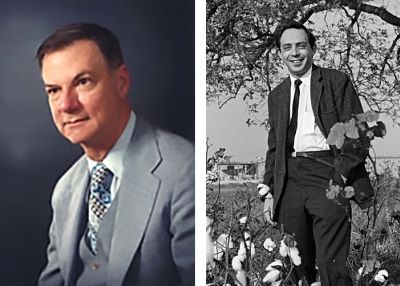

“A wild man in my office”

One day in January 1965, Lisbeth Schorr of OEO received a call from Dr. William Kissick, assistant to the U.S. Surgeon General. “There’s a wild man in my office,” Dr. Kissick told Schorr, “and he’s got some ideas we can’t do much with over here. But I think you people in the War on Poverty would find him pretty interesting. I’m sending him right over.”

Experience in South Africa

Dr. H. Jack Geiger was a Harvard University professor. He had spent time as a medical student in the 1950s in South Africa. There, he worked with Drs. Sidney and Emily Kark at the health centers they founded to provide care to patients living in housing projects and other impoverished areas. They taught Geiger about community-oriented primary care. The Karks believed in the social, cultural, economic, and political determinants of health, and Geiger would take up these ideas.

During his time in South Africa, Geiger recruited health workers from the local community. He trained them to conduct water supply surveys and address sanitation and nutrition problems. They planted vegetable gardens and built outhouses. They also collected census data and vital statistics. Using this data, health teams could predict disease outbreaks and develop ways to prevent them.

Applying the lessons closer to home

In 1964, after returning to the United States and completing his studies, Dr. Geiger was among over 100 health care workers who went to Mississippi for Freedom Summer. They were there to ensure Civil Rights workers could receive medical care. In December, Dr. Geiger attended a meeting to discuss the next steps. He started to think about how the lessons of his time in South Africa could be applied closer to home.

On the way back north, Dr. Geiger traveled with Dr. Count Gibson, head of the Department of Preventive Medicine at Tufts University. Grounded in Atlanta overnight because of fog, they kept discussing the idea of founding clinics to serve communities like the ones they had seen. Finally, Dr. Gibson said Tufts would sponsor the project if Dr. Geiger could get the money.

OEO funding

Dr. Geiger spoke with Lisbeth Schorr and Sanford Kravitz, the director of research and development at OEO. He spent two hours with Kravitz, describing his vision for community health centers. At the end of the meeting, he asked for $30,000 for a study. But Kravitz said no, that wouldn’t do. Then he explained, “Because you have to take $300,000 and do it now.”

Drs. Geiger and Gibson submitted a proposal in February 1965. That June, OEO approved a research and demonstration grant for the first two neighborhood health centers: Columbia Point Health Center in South Boston and Tufts-Delta Health Center in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. One was in the north, the other in the south. One was in an urban area, the other in a rural area.

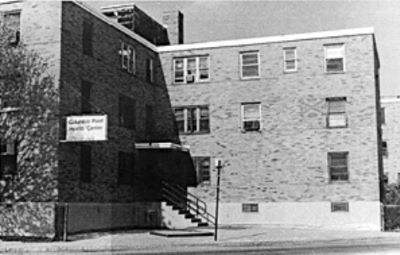

Columbia Point Health Center

In December 1965, the first health center opened in 12 converted apartments inside the Columbia Point housing project. The center hired physicians, community health nurses, nursing assistants, social workers, and community health aides. Medical students from Tufts University also assisted.

Within two years, well-child checkups and immunizations had increased. Families who postponed needed care because of cost had decreased, as had reports of excessive wait times to receive care.

Tufts-Delta Health Center

The Mississippi Delta suffered from widespread poverty in the 1960s. Many residents experienced poor housing conditions and lacked stable food and jobs. Black infant mortality was more than twice that of white infants.

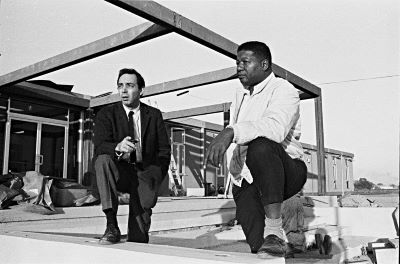

Launching the health center

Dr. Geiger began recruiting staff and organizing community resources in 1966. The first person hired was Dr. John Hatch. He was an assistant professor at Tufts who had grown up in the rural south. To identify the priorities for the new health center, Dr. Hatch crisscrossed the area and spoke with residents about their needs. The health center began providing services from a remodeled church parsonage in November 1967.

Impact of the health center

Along with medical care, health center staff worked with residents to improve sanitation. They dug wells, built outhouses, installed window screens, and fumigated houses. They also educated patients on nutrition and hygiene.

When Dr. Hatch visited communities, residents often asked for food. The health center began writing food prescriptions that could be filled at local grocery stores. When someone from OEO complained that this was not within the scope of the grant, Dr. Geiger replied: “The last time I looked in my medical textbook, the most effective therapy for malnutrition is food.”

To address food insecurity in the long term, the health center created the North Bolivar Farm Cooperative. The cooperative was owned and operated by residents. They cultivated hundreds of acres of land, growing vegetables that they froze and stored in food lockers for year-round use.

Infant mortality decreased by 57% the year the health center opened. Rates of miscarriage, infectious disease, and chronic illness also decreased.

The program takes shape

More neighborhood health centers soon followed the first two. By 1968, OEO was funding about 40 health centers. At the same time, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) began to sponsor their own. In 1968 and 1969, HEW provided grants for 24 new health centers.

Nixon Administration proposals

In the early 1970s, the Nixon Administration began transferring health centers from OEO to HEW. By 1973, all of the health centers were under HEW. They were overseen by HEW’s Bureau of Community Health Services (BCHS). The bureau also managed the National Health Service Corps, programs focused on maternal and child health, and the migrant health program.

When the neighborhood health center program came up for renewal at the end of fiscal year 1973, the Nixon Administration proposed letting it end. Nixon wanted to convert the program’s funding into block grants to the states. However, led by Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), Senator Jacob Javits (R-NY), and Representative Paul Rogers (D-FL), Congress voted to extend the program’s funding.

Formal authorization

In 1975, Congress formally authorized the program through an amendment to Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act. “Neighborhood health centers” were now formally known as “community health centers.” The law also described how health center grants were to be awarded, what services health centers needed to provide, and the requirements for health center governance.

Expanding the program

In the mid-1970s, BCHS realized that more resources needed to go to rural areas. More than half the nation’s medically underserved people lived in rural areas, but 85% of health center funds up to that time had gone to urban areas.

The Rural Health Initiative

The Rural Health Initiative began in 1975 with funding for 47 new health centers. By the next year, it had grown to 138 projects. With support from the Carter Administration, there were 262 projects in 1977 and 356 in 1978. The program’s balance began to shift, with more parts of the country gaining access to health centers.

The Urban Health Initiative

At the same time, the administration knew there was still a lot of need in urban areas. So BCHS launched the Urban Health Initiative, which funded 35 new health centers in 1977 and 60 in 1978.

The goal of both initiatives was to fund many projects, each at a relatively low budget level, to expand coverage as widely as possible. The new health centers provided basic medical care, not the comprehensive services that some earlier health centers had offered. Cost-cutting and belt-tightening were the order of the day, and this would remain the case as the program entered the 1980s.